“No library stands alone,” remarks Valerie Horton, a longtime director of library consortia. “Library cooperation goes back to the 1880s and is a long-standing tenet of the profession. Collaboration is strongly rooted in most of our current activities.” Horton goes on to suggest a number of reasons why this is so: professional networking, access to more resources, sharing expertise, prestige, and, of particular significance, economies of scale, with the promise of cost savings and the ability to reallocate resources to emerging priorities.

Horton’s observations were published in 2015, but they still resonate today as key drivers for libraries to join consortia and engage in other forms of partnership. However, collaboration comes at a cost: the direct costs of staff and other resources required to participate, as well as the indirect cost of losing some autonomy (for more on the collaboration/autonomy trade-off, see the “Coordination Spectrum” in the 2019 OCLC report Operationalizing the BIG Collective Collection: A Case Study of Consolidation vs Autonomy). Choosing to collaborate therefore becomes a strategic decision requiring careful evaluation of costs and benefits.

Prospective collaborative partners are perhaps all too cognizant of the costs of collaboration; it is therefore important to have an equally clear articulation of the benefits, especially in areas where libraries have a long history of acting autonomously. Partnership should feel not like a sacrifice of independence, but like a strategic advantage that independent action cannot match. Tina Baich, director of the Eastern Academic Scholars Trust (EAST), a shared print collaboration of more than 150 institutions, underscored the importance of clarifying the value of collaboration in a recent presentation. One key pillar of EAST’s strategy to support its organizational vision is to “Enhance the ongoing value of membership,” which includes “Communicating the value of membership” to current and prospective members. Another pillar is “Advocate on behalf of members,” which involves efforts to “Make the case for shared print.” In both cases, there is a need to understand and communicate the motivations (and ultimately, the potential benefits) for institutions to partner around print stewardship.

Insights from shared print

Recent evidence gathered by OCLC Research offers concrete examples of what these compelling motivations look like in practice in the context of shared print programs.

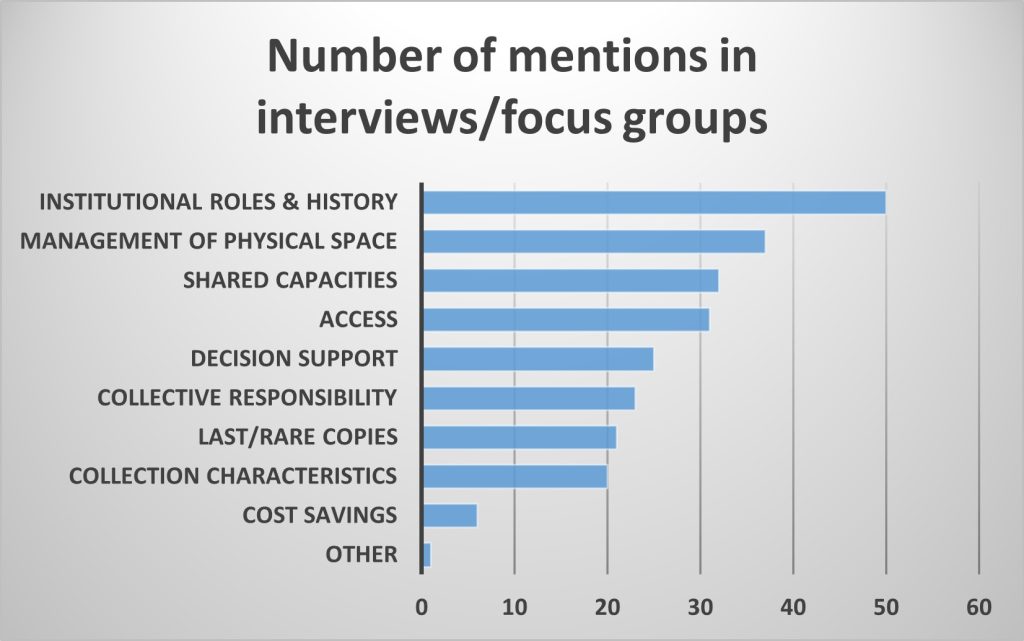

Stewardship of print collections is an excellent illustration of an activity that libraries have traditionally carried out at local scale, but for which they are now adopting collaborative approaches at group scale. What are the motivations exerting sufficient gravitational force to pull libraries away from long-standing local-scale approaches? We touched on this question in the project Stewarding Collective Collections: US and Canadian Perspectives on Workflows, Data, and Tools for Shared Print, in which we gathered insights from staff at shared print programs and participating institutions on a number of topics, including the motivations for managing print monographs collectively—an important area of library collaboration.

For this project, we spoke to a total of 37 people through focus groups and individual interviews, gathering perspective from individuals from institutions participating in monographic shared print efforts—deans/directors, AULs for collections, collections librarians/strategists, metadata librarians, and resource sharing librarians. We also talked with staff from monographic shared print programs—primarily program managers—from a number of North American partnerships.

What we found

Our interviewees discussed key reasons for participating in or operating shared print programs. The most frequently mentioned were institutional roles and histories, including previous institutional experiences in collaborative collection stewardship—or collaboration of any kind. According to our interviewees, institutions that have previously invested themselves in some form of collective action are often more open to opportunities for new collaborations, such as shared print. This is especially true when members participate in consortium-sponsored shared print programs. Past experiences and established collaborative infrastructure within the consortium build trust and confidence in collective endeavors. We have described this elsewhere as acquiring an option to collaborate, where past collaborative efforts create the option to engage in future collaborative opportunities.

Several interviewees also mentioned that their status as the only or the largest institution in the region led to a sense of obligation to participate in shared print efforts.

The second most frequently mentioned incentive to join shared print programs was management of physical space—the opportunity to reduce the print collection’s physical footprint in the library, releasing space for other uses. Access to shared capacities (storage facilities, technical systems, aggregated data) was another top response, highlighting a desire for greater efficiency beyond what is achievable through local-scale implementations. Moreover, shared approaches may be the only feasible option for some institutions to obtain these capacities.

Next on the list of key drivers for participating in shared print efforts was access to holdings beyond the local collection. This response touches on a key principle behind collective collections—the idea that managing holdings collectively not only makes stewardship more efficient, but also removes barriers to discovery, delivery, and ultimately, greater use. Another incentive was the opportunity for greater decision support: using collective collection analysis to inform local collection decision-making, such as weeding, moving materials to off-site storage, and acquisition strategies.

The next two drivers mentioned by our interviewees rise above local interests to touch on opportunities to advance the common good. One is recognition of a collective responsibility to steward the print published record, an objective that can only be truly achieved by the combined efforts of many institutions working toward this common purpose. Related to this, interviewees also mentioned a desire to safeguard last or rare copies of print publications, which often can only be identified at scale, where the individual distinctiveness of local print book collections aggregates into a rich and diverse long tail of rare or even unique materials within the collective collection.

Interviewees also highlighted the importance of collection characteristics as another important factor impacting engagement in shared print efforts. Institutions that specialize in collecting in certain subject areas—like the arts or medicine—can become important strategic partners in broader, multi-institutional shared print efforts, in which specialized collections complement the holdings of other institutions. It is the broader context of a collective collection that amplifies the visibility of these local strengths.

Perhaps surprisingly, direct mention of cost savings—lowering the cost of managing print monographs through collaboration—was relatively infrequent among our interviewees. This suggests that institutions often enter shared print partnerships for non-economic reasons, although some motivations, such as shared capacities, may have implicit cost considerations.

Data-driven analysis is key for incentivizing collaboration

While not comprehensive of all incentives, these findings are indicative of some of the major factors that drive participation in shared print programs. The golden thread that runs through many of them is the importance of data-driven analysis to highlight and clarify untapped opportunities to create, expand, or optimize shared print efforts.

Want to know how participation in a shared print program will help release space for new uses? Data-driven analysis can clarify the extent of redundancy across a group’s collective print monograph holdings, identifying candidate materials for deaccessioning or removal to off-site storage. Are you interested in how the characteristics of your local print collection stack up against those of your shared print partners? Data-driven analysis can help identify potential complementarities and unique strengths, providing strategic intelligence to inform local collection development. Wondering if your collection contains hidden gems—rare or even uniquely held materials—that warrant special stewardship attention? Data-driven analysis of group- or even global-scale holdings can answer that question.

Aggregated data, combined with analytic tools that can turn it into actionable intelligence, is essential for identifying and communicating the key motivations for participation in shared print programs. These analytical approaches create the evidence needed to show how participation in collective stewardship efforts around print holdings creates value across the partnership. In doing so, they help libraries choose their collaborations strategically, through evidence-based evaluation of the incentives to join. And for shared print programs, this approach sharpens the benefits, makes them more visible, and transforms collective stewardship from an ideal into a demonstrable asset.

The importance of data-driven analysis is a key finding of our Stewarding the Collective Collection project. Our conversations with interviewees made clear that shared print is first and foremost a data-driven activity—collecting, organizing, and analyzing data about groups of collections. Shared print collections are often decentralized across many local collections, rather than existing as physically consolidated collections; in this sense, they exist, for all practical purposes, as constructs in data. Reliable data and analytical tools are therefore indispensable for successful shared print programs.

This finding was echoed in another OCLC Research study, which explored collaboration opportunities for specialized art research libraries. This study found:

“Collaboration is an important strategy for art libraries as they seek sustainability in a dynamic environment. . . . This report uses bibliographic, holdings, and ILL data to document potential opportunities for collaborative activity around art research collections. Indeed, our study of the proxy art research collective collection indicates . . . that art libraries bring a sizable group of rare or unique materials to the table that are not in other collections. And this creates demonstrable value: our study of ILL transactions found that most ILL transactions involving art libraries were for materials not owned by the borrowing institution. This is a classic case of value created through collaboration—specifically, resource sharing broadens the scope of the local collections of all partners.”

Like our shared print findings, this analysis identifying opportunities for art libraries to collaborate was conducted under the auspices of a research project. Fortunately, libraries now have the capacity to carry out similar analyses themselves, using WorldCat-powered tools like Choreo Insights and GreenGlass. So, when the question “Why collaborate?” is posed, we have answers. Evidence is always more persuasive than exhortation.

Valerie Horton notes that, “in the end, the reason so many libraries join together is to achieve more than any library can achieve on its own. The era of the library consortia is not ending; instead it is set for a transformation as technology has removed many of the physical barriers to collaboration that distance formerly created.” Data-driven technologies, like collection analysis tools, are yet another transformation that diminishes the barriers to collaboration—in this case, by clarifying the incentives to participate in collective stewardship efforts like shared print.

Stay tuned for more findings from the Stewarding the Collective Collection Project!

Many thanks to the participants in our interviews and focus groups whose insight is shared in this post!

Brian Lavoie is a Research Scientist in OCLC Research. He has worked on projects in many areas, such as digital preservation, cooperative print management, and data-mining of bibliographic resources. He was a co-founder of the working group that developed the PREMIS Data Dictionary for preservation metadata, and served as co-chair of a US National Science Foundation blue-ribbon task force on economically sustainable digital preservation. Brian’s academic background is in economics; he has a Ph.D. in agricultural economics. Brian’s current research interests include stewardship of the evolving scholarly record, analysis of collective collections, and the system-wide organization of library resources.