Many libraries and archives are homes for oral history programs. Oral histories add voice, personality, richness, and depth, and are a natural complement to other types of collections. While these narratives can bring significant value to collections, supporting oral history production can present special challenges. Oral history programs can be composed of complex, multi-stage projects that require thoughtful planning, coordination, and even innovative approaches to capture, preserve, and make accessible valuable cultural and historical narratives.

In a Works in Progress webinar hosted by the OCLC Research Library Partnership (RLP) on 21 October 2025, practitioners from the University of Washington and Montana State University shared their experiences developing and implementing effective oral history program workflows, which now includes best practices for balancing human expertise with emerging AI technologies.

Conor Casey, Head of the Labor Archives of Washington at University of Washington Libraries Special Collections, shared his experiences based on over 13 years of evolved practices with collaborative workflows and scalable project management. The Montana State University team—Jodi Allison-Bunnell, Head of Archives and Special Collections; Emily O’Brien, Metadata and Mendery Specialist; and Taylor Boyd, Metadata & Collection Support Technician—discussed their experiments using two different tools to generate oral history abstracts.

This blog post summarizes the webinar’s key insights, but you can watch the full recording right here.

The Labor Archives of Washington: Shared stewardship in practice

The Labor Archives of Washington, founded in 2010 as a partnership between the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies and UW Libraries Special Collections, demonstrates how community-founded archives can scale oral history programs through strategic collaboration. Despite never having more than two full-time staff members (who also have other duties and responsibilities), the archive has completed close to 200 interviews across multiple projects by leveraging a collaborative model that designates clear roles for all players.

Scaling through partnership and project management

Conor Casey emphasized that success stems from recognizing institutional strengths and distributing work accordingly. The archive provides infrastructure, tools, and preservation expertise; community partners bring connections to narrators, scholarly expertise, and cultural knowledge essential for developing interview questions that are meaningful within the user base.

The Labor Archive’s workflow success relies on project management tools, including Asana templates, Google Drive file management, and comprehensive documentation. As an example of how documentation and project management tools work to ensure a smooth experience, Casey stressed the importance of “baking in” permissions, requiring signed release forms from participants before embarking on a project to enable stewardship of a given collection. These tools also ensure quality and consistency in metadata.

Ensuring that all parties are on the same page is also vitally important. Casey advised that clear roles and deadlines to keep the project on track, and that project charters or MOUs can be very helpful when collaborating between organizations and with multiple parties, even within organizations.

Even with AI promise, transcription remains a human-centered activity

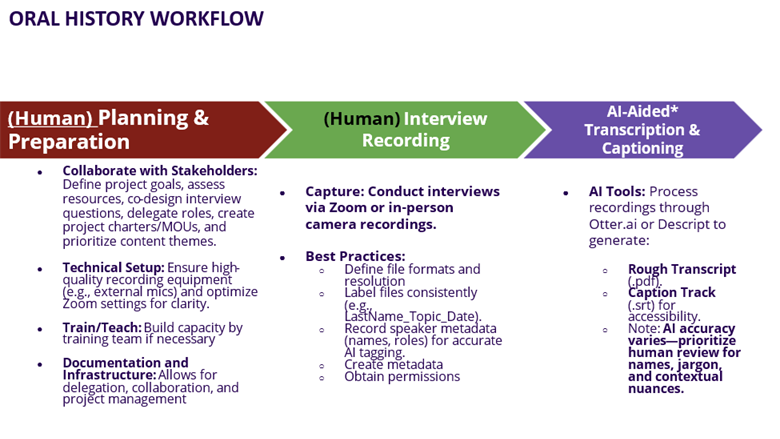

Beginning in 2018, the Labor Archives began experimenting with AI-aided transcription using tools like Otter.ai, Maestra, and Descript. These tools are not one-size-fits-all solutions and depend heavily on project needs. When AI is employed, Casey’s workflow diagrams revealed a crucial insight: human intervention appears at nearly every stage of the AI-aided process.

Despite the promise of AI in some cases, a professional transcriptionist is still faster and more accurate for certain projects. “Professional transcribers may still be more efficient than just AI,” Casey noted. “You are still going to have to do a lot of work to correct, tag, and conform AI to transcription style guides.”

Accessibility is core to mission

Casey also discussed the implementation of many accessibility features, such as including transcriptions and captioned media for all interviews. Casey positioned accessibility not as an add-on compliance requirement, but as central to the archival mission. The archive proactively implemented transcription and captioning before Washington State’s 2017 mandate for all new online projects, viewing these activities as extensions of intellectual access rather than a burden.

Montana State University: AI to support accessibility needs

The Montana State University team faced a specific challenge: creating abstracts for approximately 350 oral history recordings in their Trout and Salmonid collection to meet ADA Title II accessibility requirements. The MSU library staff were very much encouraged by leadership to embark on a journey of learning around AI tools, so experimenting with tools to learn (and employing exploration and curiosity along the way) was a natural step for the team and the framework for their presentation and discussion overall.

These field recordings from around the world presented unique challenges, including:

- Multilingual interviews conducted with interpreters

- Variable field recording quality

- Videos that had been edited to include interviewer questions only on text intertitles

Jodi Allison-Bunnell spoke about using Claude.ai to generate 200-word abstracts from full transcripts produced in Trint. The team found that Claude generally produced coherent abstracts. However, several limitations emerged:

- Missing context: Because interviewer questions were only shown on intertitle slides, Claude struggled to provide complete context

- Factual error: If proper names and technical terms were incorrect in the transcript, they were also in the abstract; the transcript had to be thoroughly reviewed to avoid promulgating errors

- Over-inference: When given insufficient content, Claude would sometimes infer more about subjects than was supported by the source material and required a human with good knowledge of the transcript to intercept and correct the imbalance

The cataloger perspective: Quality and workflow integration

Emily O’Brien and Taylor Boyd assessed the abstracts from a metadata creation standpoint, focusing on whether AI-generated abstracts contained sufficient information for accurate cataloging without requiring catalogers to repeat work.

For this specific use case, Trint consistently outperformed Claude, Gemini, and ChatGPT. However, caution should be applied before declaring a clear and persistent winner in an area where tools and technology are evolving quickly. The team found that Claude abstracts generated months apart showed significant quality differences; this finding demonstrates that it is difficult to make static judgments about tools in this quickly evolving space.

O’Brien and Boyd also emphasized a vital point in assessing the accuracy and efficacy of AI-generated abstracts that will support metadata creation: unless AI-assisted humans have prior learned experience with creating abstract-level metadata, they make lack the ability to assess the quality of AI outputs.

Despite limitations, the team found significant time savings. Reading a transcript and writing an abstract from scratch took, on average, 1-2 hours, while reading a transcript, running it through Claude or Trint, and assessing and correcting the result took an average of 30 minutes. However, Allison-Bunnell also highlighted the need to maintain oversight over tools (including changes in terms of service) and to budget time to review workflows that might be impacted by those changes, as well as to develop, implement, and review AI use policies on an ongoing basis. Ultimately, time savings may be shifted across positions in ways that aren’t initially evident.

Lessons learned and workflow implications

Both presentations emphasized that effective workflows supported by AI require human oversight at multiple stages. The Labor Archives workflows reflect human intervention points throughout the process, while the Montana State team stressed that professional experience in the relevant domain is essential before AI tools can be effectively evaluated or implemented.

Successful oral history workflows cannot be separated from organizational context, resources, and mission. The Labor Archives’ collaborative model works because of their community-focused mission and partnership infrastructure. Montana State’s approach is grounded in their need to meet specific accessibility requirements and also in their deep collection strengths supported by corresponding curatorial and community knowledge. Both institutions demonstrated how accessibility considerations drive innovation rather than constrain it.

Looking forward

These presentations illustrated that effective oral history workflows require thoughtful integration of human expertise, technology, and collaborative partnerships. AI tools can enhance efficiency and accessibility, but they work best when implemented with a clear understanding of their limitations and within robust frameworks that center human knowledge.

The key insight across both presentations was that technology should amplify human-centered values and good project design, not replace them. Successful oral history programs leverage innovation in service of their core mission: preserving and providing access to irreplaceable cultural narratives. These presentations demonstrate the value of taking a stance of curiosity, exploring, and sharing our experiments and lessons learned as we navigate the integration of new technologies with traditional archival practice. We would love to hear about your experiments in this area!

—

Special thanks to Conor Casey, Jodi Allison-Bunnell, Emily O’Brien, and Taylor Boyd for generously sharing their insights and experiences. For more resources on oral history workflows, including templates and project management tools, view the slides and watch the full webinar recording from the event page.

Merrilee Proffitt is Senior Manager for the OCLC RLP. She provides community development skills and expert support to institutions within the OCLC Research Library Partnership.

By submitting this comment, you confirm that you have read, understand, and agree to the Code of Conduct and Terms of Use. All personal data you transfer will be handled by OCLC in accordance with its Privacy Statement.