The following post is part of series highlighting OCLC Research’s efforts for the Building a National Finding Aid Network (NAFAN) project.

Cytonn Photography. Free use image from UnSplash.

One major challenge for the NAFAN project is the lack of information about the users of archival aggregation sites. Past research is dominated by one-time studies. We’ve talked at greater depth on this in previous blog posts in this series.

The lack of data about users and user behavior is perhaps not surprising given the amount of work it takes to just keep the lights on. Sustaining archival aggregation requires constant attention to the contributor network, normalizing finding aid data, and often requires maintenance for aging infrastructure. With these challenges in mind, OCLC Research designed a study that takes a comprehensive approach to understanding the breadth of users and the depth of their search behavior across different aggregators. The project is more than just a retrospective study. The information we collect through this project is a key component to the design of a new national portal for users to access aggregated archival information. For this study we are gathering information using a variety of methods, including point-of-service pop-up surveys, virtual focus group interviews with cultural heritage professionals that work with archival materials and create finding aids, and in-depth individual interviews with users of archival aggregation sites. This post focuses on the information gleaned from the pop-up survey. Subsequent blogs will highlight findings from data that were gathered using different qualitative methods.

Method

To gather information about users and user behavior across sites, we asked all 13 archival aggregators participating in the grant to host the pop-up survey on their sites.

There were a few challenges we had to work through in designing our data collection strategy. One of the most important was determining how to get a sample of the general population that visit and conduct research on the sites. For 8 of the participating aggregators with lower traffic, the pop-up survey appeared for every user, and individuals were free to opt-in or choose not to take the survey. For 5 sites with a higher frequency of use, the pop-up survey appeared for every other user of the site. We chose this strategy to provide an opportunity for a broad cross-section of users to respond. We had considered a targeted probability-based sampling approach at the outset. But without prior studies detailing the population of users of archival aggregation sites, there was no way to develop the probabilistic mechanisms for sample selection; therefore, we used convenience sampling. While the inability to make an inference from the data presents a challenge, we knew that there still were many important uses of the data from a convenience sample. For example, as an early study that looks across multiple aggregators, the data would be helpful in developing new research hypotheses and defining general tendencies and ranges of responses. It also was a unique opportunity to look at user responses across multiple aggregators.

We set an initial national target for 1,000 total responses. Given the wide variability in use rates across aggregators, which ranged from 20 to 141,000 per month, we knew it would be impossible to get comparable response numbers across all sites using the same collection period and concluded that a strategy of blanketing respondents across most sites would provide the greatest flexibility for subsequent research. The total survey response far exceeded expectations with 3,300 complete responses across all sites.

Data collection started on March 19, 2021. Some aggregators implemented the pop-up survey link at a slightly later date. The entire data collection period spanned two months with each aggregator holding their survey open for at least six weeks. The pop-up survey was posted on aggregator portals on the homepage, on search results pages, and on the landing page for each finding aid published within the aggregator system.

Who are the users of archival aggregation sites?

Below are findings from the survey. These are key takeaways that help to describe the pop-up survey respondents, and should not be used to generalize to all archival users.

Chart 1 below shows all reported professions ranked from most frequently reported professions to the least frequently reported. The highest portion of survey respondents (20.8%) reported that they had retired from full time employment. Chart 2 below shows that 56.8% of respondents are over 55 years old, which is consistent with the fact that a large number of respondents reported that they are retired.

Interestingly, the next highest ranked profession is information professionals; librarians and archivists make up 13.5% of respondents. We know from contextual information that archivists and librarians visit aggregation sites to fulfill daily work-related responsibilities such as reference work for users or collection development. Roughly one-third of respondents work in various professions where research in archives is common such as faculty and academic researchers, graduate students, genealogists and undergraduate students.

The professions representing less than 5% of respondents includes journalists, writers, artists, filmmakers, museum professionals, K-12 educators, historians, and independent researchers.

Given the reported age distribution (Chart 2), it also appears that the highest percentage of respondents are also the oldest (65+ years old). Below the age of 55, the next highest group of respondents is aged 45-54 at 14.5%, followed by 10.6% of respondents in the 35-44 age range. Roughly the same percentage of respondents indicated they were undergraduate students (5.9%) who reported they are 19-25 years of age (6.2%).

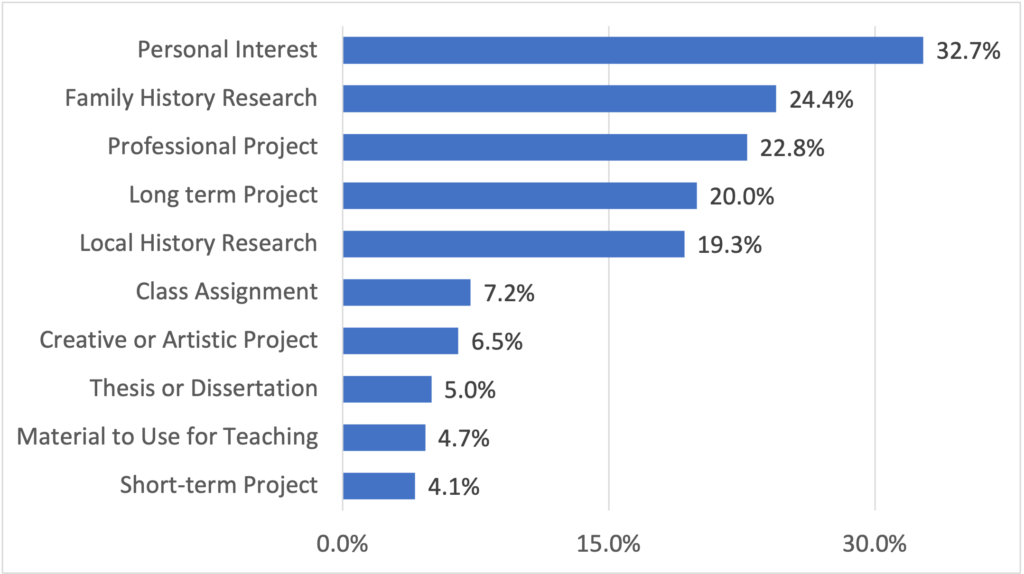

When asking respondents to report their purpose for using an archival aggregation website, we allowed them to select more than one topical or thematic area. In Chart 3 below, the reasons reported for visiting the aggregation site include a mix of personal and professional uses. Some of these uses are short-term in nature, such as school assignments, newspaper articles, and thesis. Others are longer in nature and may require several visits. These uses appear more frequently (each more than 19%) and included uses like book projects, family history and local history research. When compared to the professions in Chart 1, it also is easy to associate some of these long-term projects with the work of academics, professionals, archivists and genealogists.

Totals do not sum to 100%. Long-term projects include books, documentaries or other projects that take months or years. Short-term projects include news articles, television projects, or other projects that take days or weeks.

Nearly half of respondents (42.7%) indicated that they preferred online materials but were willing to use in-person materials. Roughly a quarter of the respondents (23.6%) indicated they had no preference between online or in-person materials. Roughly the same number of respondents stated a strong preference for online only (14.4%) as those that prefer in-person only (14.7%).

Look for more posts in this series on other parts of the Building a National Finding Aid Network project from OCLC Research.

Acknowledgements: I want to thank my project team colleagues, Chela Scott Weber, Lynn Silipigni Connaway, Chris Cyr, Brittany Brannon, and Merrilee Proffitt for their assistance with the survey data collection and analysis; OCLC Research colleagues that reviewed the draft pop-up survey questionnaire; and, Chela, Lynn, and Merrilee for their review of this blog post. We also want to thank the respondents for taking the time to support our research efforts and complete the survey.